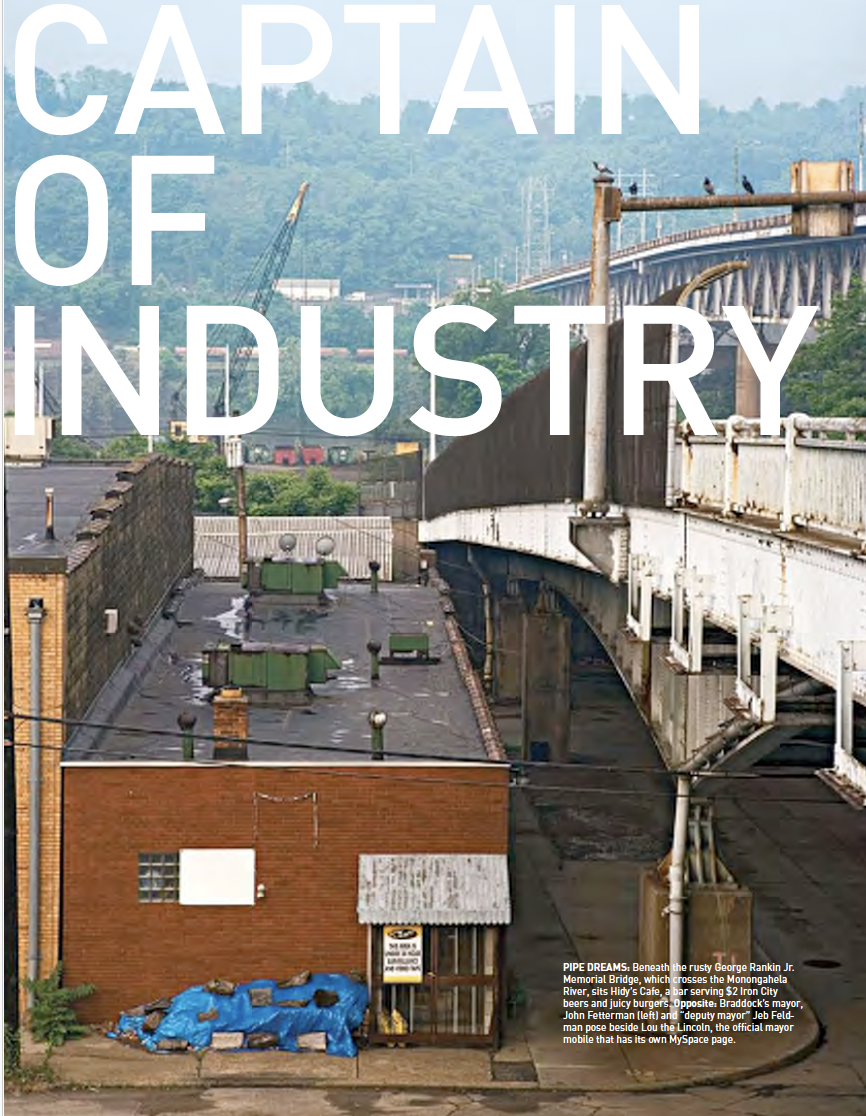

Captain of Industry: John Fetterman’s Mission to Save Braddock, Pennsylvania | ReadyMade Magazine

This article was originally published in ReadyMade magazine in 2007. I was one of the first journalists to do a national story on John Fetterman. Fun fact: The publication of this article led to him meeting his wife.

On a bright spring morning, a day built for wearing shorts and playing hooky, finding the six-foot-eight, 300-pound mayor of Braddock, Pennsylvania, is surprisingly tricky. Calling his office or swinging by his cinderblock home crowned with shipping containers will prove fruitless. Instead, the elusive mayor is wearing shorts and an oversize T-shirt, standing knee-deep in black roof shingles ripped from a home he’s remodeling.

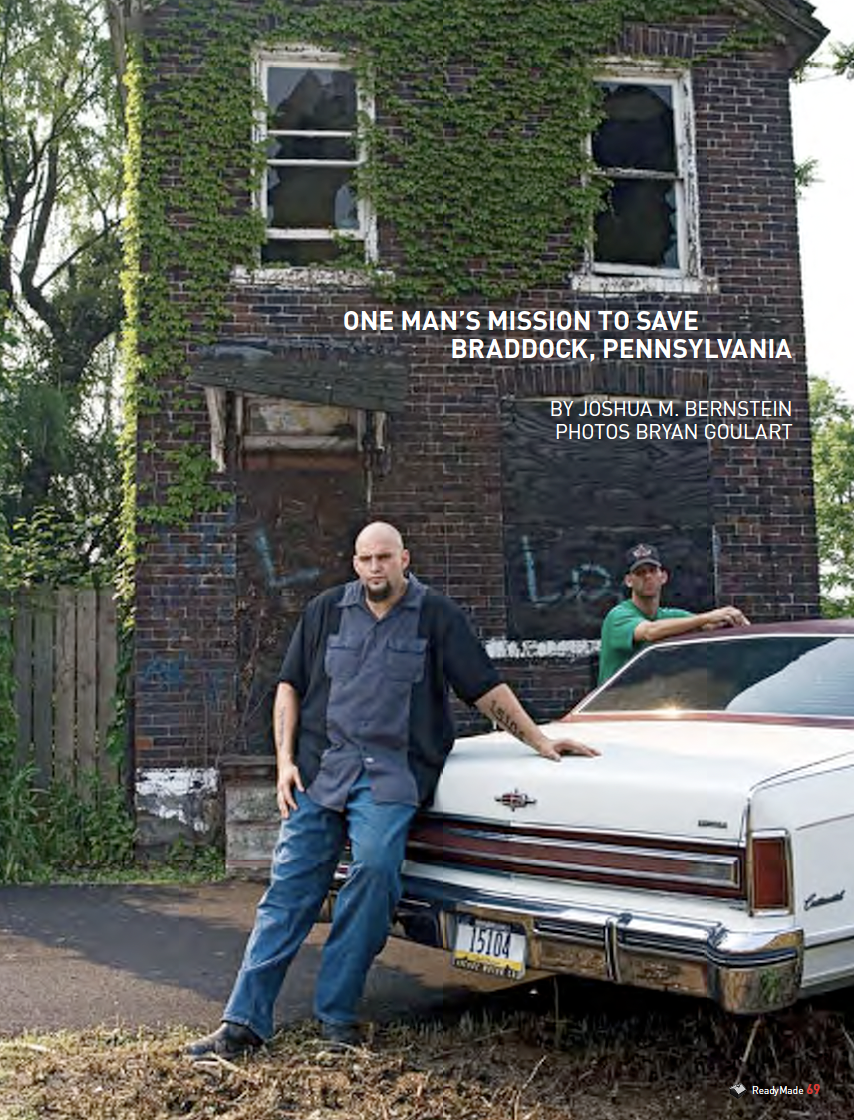

“If I’m not getting dirty, I’m not doing my job. Wearing a suit and tie doesn’t work for me,” says the 37-year-old John Fetterman, whose cue-ball skull, bristly goatee, callused hands and right-forearm tattoo of Braddock’s zip code, 15104, are more apt for the World Wrestling Federation than elected office. That is, elected office anywhere besides Braddock.

In the 1920s, this Pennsylvania town located 20 minutes outside Pittsburgh was a booming steel-making community of 20,000 crammed into a half-mile square; population density trumped modern-day Brooklyn’s. Braddock’s riches included Andrew Carnegie’s first steel factory and free library, and lively Braddock Avenue was a shopping destination where couples and families caught dinner and a movie. “I wish I could go back in time to see how bustling this town once was,” says Fetterman wistfully.

When the steel industry tanked in the ’70s, folks and businesses fled. In came Crips gangsters, unofficially renaming Braddock Braddocc in graffiti around town. Now, fewer than 3,000 people dwell in this scarred ghost town rife with charred, roofless buildings. Braddock Avenue looks tornado-battered, with windowless, half-collapsed storefronts and the random pawn shop, donut luncheonette or bar clinging to solvency. More than 300 of Braddock’s buildings are slated for demolition, and if structures aren’t disappearing, then people are: 2005 saw sixteen murders in Braddock and neighboring North Braddock.

“It’s hard to find a town that has tanked as severely and completely as Braddock,” says Fetterman, who became mayor in 2005—by one vote. He beat the incumbent despite having never held public office. But because Braddock is a borough, his powers are limited (managing police, basically) and pay is low (about $150 monthly). Nonetheless, Fetterman’s ambition is limitless.

Where some see another terminally ill industrial city, Fetterman envisions a stage for experimental urbanism, emphasizing communal living, urban gardens, green space and arts, glued together with do-it-yourself sweaty equity. “Destruction breeds creation; create amidst destruction,” says the mayor, gazing at the still-functioning steel factory Edgar Thomson Works, whose 40-foot flames periodically lick the night sky. “We’re in the Wild West here.”

Fetterman came to Braddock in 2001 to launch a program helping disenfranchised kids get their GEDs—“the very people who eventually voted me mayor,” says Fetterman, who graduated from Harvard with a master’s in public policy and economics. Enamored of the town’s “malignant beauty,” which sees ivy crawling up crumbling buildings splashed with vibrant graffiti, he moved to Braddock permanently in 2004.

He planted a flag on centrally located Library Street, lent its name by the still-operating Carnegie Library. With family money, Fetterman purchased the empty, stained-glass-decorated First Presbyterian Church “for what storage closets cost in Manhattan”—$50,000. He squatted in the icy basement for eight months, before moving into the adjacent warehouse (which he topped with two, 50-foot shipping containers for extra living space), a pre-existing structure purchased for $2,000.

It’s decorated with stainless steel countertops, salvaged-tin ceilings and black-and-white pictures of dilapidated Braddock buildings that have been demolished, while the first floor holds Dorothy 6, a gallery named after a famous steel factory’s blast furnace (street artist Swoon held a show last spring, and her ethereal paper cut-outs remain wheat-pasted around town). Soon, Fetterman snagged and fixed up several more homes, too. “The opportunity to reclaim old spaces is like a drug for me,” says Fetterman, who spends his days scouting reclamation sites. Homes can be bought for $10,000, a trifle compared to about $160,000 for a three-family home in Pittsburgh.

It’s fortunate Fetterman is interested, because “nobody else wants to live here,” jokes Jeb Feldman, Fetterman’s honorific “deputy mayor” and right-hand man. Feldman, who is in the process of buying a Braddock home, is wiry, prone to wearing trucker caps and cruises around town with the mayor in a white Lincoln Continental (license plate: 15104). “It’s unpretentious and a totally unique.” Feldman says of the car. “Just like Braddock.”

What can Fetterman offer to entice a new generation to this crumbling city? Space and cheap rent, long-time irresistible lures for artists who often can’t afford to live in well-appointed urban enclaves. So, Fetterman thought, “Let’s insert art into Braddock and see what happens.” The mayor provided free studios in an empty, eight-story furniture warehouse to photographers and painters (the building was unused, so owner Brandywine Management allowed Fetterman to donate the space). The church became a free-for-everyone community space, recently holding avant-garde art events, elementary-school art shows (including wire sculptures and colorful paintings) and all-night dances attracting partygoers from the Pittsburgh region.

“I control the police department, so people don’t need to navigate a Byzantine maze of red tape to throw events,” says Fetterman with a laugh. Securing building permits is also a snap. “I just call up my guy and say, ‘Hey, I’m going to be renovating this house,’ and I have my permit,” says Fetterman.

During this hot May day, he and Feldman, along with Fetterman’s sister, Kristin, and her carpenter boyfriend are renovating a brick home with wood floors and beautiful moldings near the steel plant. Everyone’s chipping in, hoisting large sheets of Plywood onto the roof. Their goal is to create a communal space for artists (or, heck, anyone), who will pay about $50 a month and tend to a backyard vegetable garden. Kristin and her boyfriend will be tenants.

“We’re amazed by how far John has come—and we wanted to be a part of it,” says Kristin, an artist, who was priced out of Portland, Oregon.

But you can’t build a town on family alone. You need businesses to create a new economic base. Fossil Free Fuels, which outfits cars with vegetable-oil fuel systems, recently moved into a multilevel former electronics store. Co-owners Colin Huwyler and David Rosenstraus were drawn to Braddock’s big-city proximity, cheap rent ($890 per month) and Fetterman’s added-value benefit. “John went above and beyond to get us to Braddock,” says Huwyler of the mayor, who provided the twosome rent-free lodgings for a year.

“We’re a concierge,” explains Feldman. “We’re here make you happy and accommodate you.”

What makes Feldman and Fetterman unhappy is the proposed Mon-Fayette Expressway. This megalane monstrosity, percolating in Pennsylvania’s Turnpike Commission since the 1950s but still lacking funding, would scythe through Braddock’s downtown. “These are Robert Moses tactics,” Fetterman says, referencing New York City’s “master developer” responsible for shoehorning freeways into neighborhoods. “I’d rather chain myself to a bulldozer before someone runs a four-lane highway through my town.”

Still, the Mon-Fayette’s specter means property owners have long awaited hefty paydays from the state for properties acquired via eminent domain, in which the state takes homes for public-use projects. Anticipating demolition, owners let countless structures deteriorate. “Many buildings, they’re just lost,” says Fetterman, who battles both the elements—“a good roof would’ve saved most buildings”—and unscrupulous scavengers.

“We constantly fighting midnight plumbers,” says Fetterman, referencing scavengers who rip out copper pipes for salvage. It’s not uncommon to see men cruising in a pickup, old appliances piled willy-nilly, breaking into decrepit structures and dragging out stoves. Neighbors typically ignore the pillaging. Fetterman notes this grimly. “We need to get people excited about living in Braddock again,” adding, “For DIY-ers, this town is a dream,” he says.

Locals, however, are cautiously enthusiastic about Fetterman’s plans for Braddock. “It’s difficult to change people’s minds about what the town can be, that it can be something again,” says Vicki Vargo, executive director of the Carnegie Library.

“More power to him, because nothing much has happened here in years, but he’s got a long, hard road to bring Braddock back,” says Mark Mattis, who has bartended at Budweiser-and-pool dive Hotel Puhala for nearly 20 years.

And Fetterman, for all his efforts, can’t spruce up every home on his own dime. Outside creative and economic capital is required. So along with hands-on projects Fetterman’s days are spent as Braddock ambassador: On a typical day, he’ll meet clothing designers hungry for an apartment and museum honchos eager to launch experimental programs in which struggling artists are bought homes in Braddock. The interest is mostly regional, spurred by articles in local newspapers, the town’s edgy, informative Web site and Feldman’s outreach lectures. Any idea is considered, everybody is welcome to visit, though Fetterman’s loath to call such efforts a “gentrification initiative.”

He encourages all-night dance parties, sure, but he also hosts family reunions, plants gardens and trees, and has seen crime drop (from 16 to four murders since he assumed office, the date of each tattooed on his right forearm, though he doesn’t take credit for the decrease). Despite Fetterman’s commitment to community-building, he still butts heads with Braddock Borough Council. The six-person governing body, which wields Braddock’s governmental power, appreciates his energy and efforts, yet would rather he concentrate on mayoral duties and attend monthly Council meetings instead of being “aloof” and “in a world of his own,” as Council President Jesse Brown has accused Fetterman.

“We’re not bowling buddies,” the mayor allows.

But with no previous governing experience and little more than a glimmer of what could be to guide him, Fetterman has no hard-and-fast rules for Braddock’s future, or even a master plan. He knows it’ll never again be an industrial powerhouse, but what it can become is an ever-evolving experiment.

“Braddock is big enough to matter, but small enough where we can see our initiatives’ outcomes; if they don’t work, we’ll try something else,” he says. “I’m nothing but a third-rate mayor, but I’m doing everything a third-rate mayor can for Braddock.”